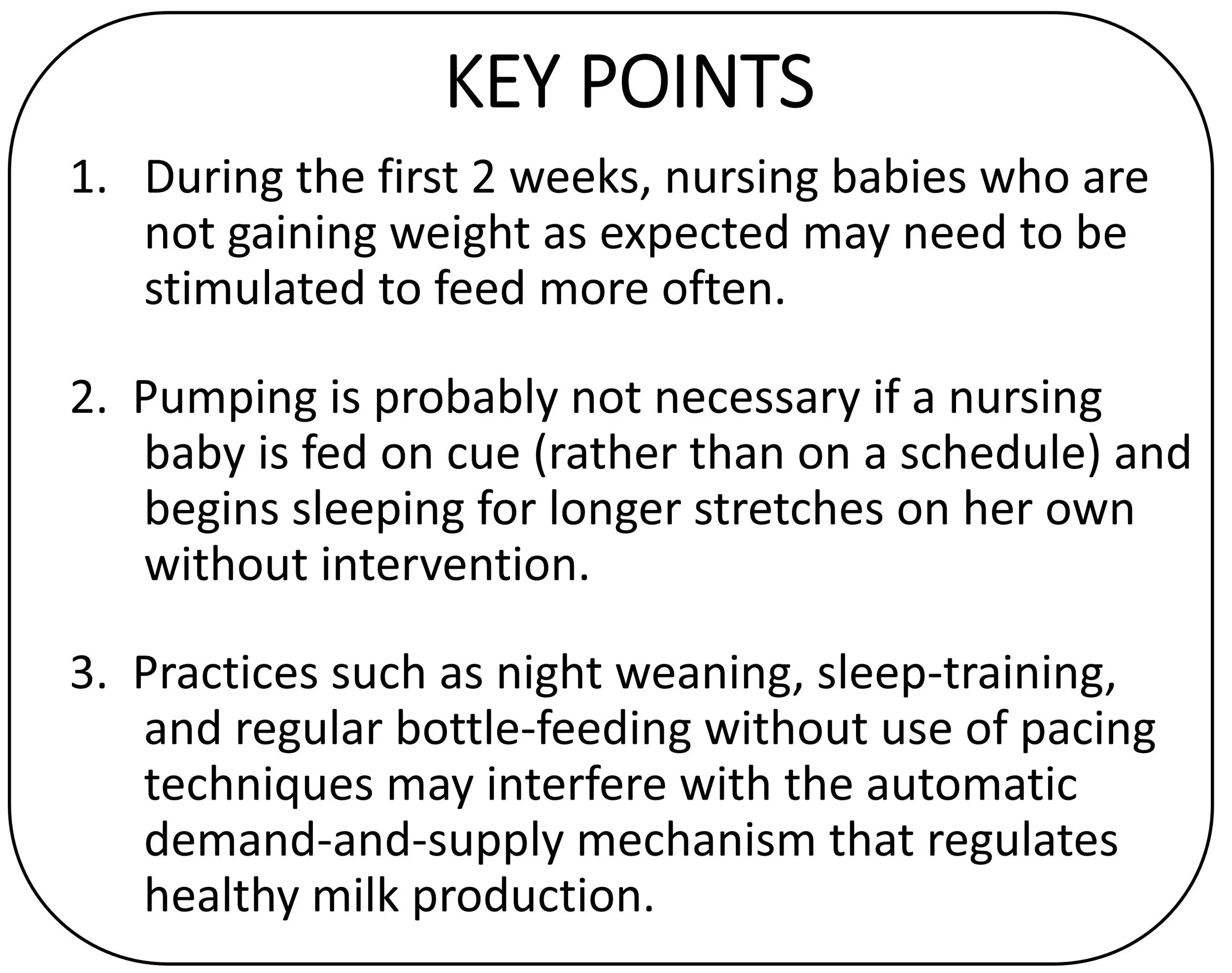

Myth or Fact: Never Wake a Sleeping Baby

/When it comes to sleep and babies, parents often get conflicting advice. Should a sleeping baby be awakened every few hours to nurse? If a baby begins sleeping longer stretches, is pumping necessary to maintain milk production? As with many baby-care questions, the answer is “it depends.”

When babies sleep for long stretches, several factors influence the best course of action: your comfort, baby’s age, and baby’s growth. Some common practices may also affect these decisions. Let’s start with the basics.

Your Comfort

No matter what is going on with your sleeping baby, if you wake up feeling uncomfortably full of milk, it’s time to take action. Go ahead and nurse. You can do this without fully awakening your baby by encouraging what’s called a “dream feed.” This means stimulating your baby just enough during light sleep (eyes moving under eyelids, any body movement) to latch and nurse but not so much that she is wide awake. After dream feeds, babies usually continue sleeping. This kind of turnabout is fair play, as baby likely wakes you when she needs to nurse. The longer unrelieved breast fullness continues, the greater the risk you’ll develop a problem, such as plugged ducts or mastitis. Your health is important, too!

Baby’s Age and Weight

In addition to your needs, are there times when—for baby’s sake—you should awaken a sleeping baby to feed? Yes. Most often, this need arises during the early weeks.

Early weight loss and gain. After birth, nursing babies commonly lose up to 10% of birth weight,[1] with the lowest weight occurring on Day 3 or 4. From that point on, babies gain on average about 1 oz. (30 g) per day until they reach 3 or 4 months of age, when weight gain naturally slows.[2] It’s a good sign if baby is back to birth weight by 2 weeks, but some well babies may take longer than this. Most health organizations recommend babies see their healthcare provider for weight checks within a day or two after hospital discharge and again at around 2 weeks. Weight gain is the most reliable gauge of how nursing is going.

The first 2 weeks are like a “trial period,” when it’s a good idea to keep a close eye on the nursing baby. This usually involves weight checks, tracking number of nursing sessions per 24 hours and diaper output. If baby is not gaining weight as expected or has a weight loss of more than 10% of birth weight, it’s time to see a lactation specialist to determine the cause. In some cases, this is unrelated to nursing (see HERE). But it may happen if a baby spends too much time sleeping and not enough time nursing. An overdressed or swaddled baby may become too warm (for more on swaddling, click HERE), which increases sleepiness (use adult clothing weight as a guide for baby). Some newborns don’t nurse effectively due to a shallow latch or other issues, which can contribute to both weight-gain issues and nipple pain in the nursing parent. When an ineffective baby’s resulting calorie intake is too low, this not only causes weight issues, it saps her energy, causing excessively sleepiness.

Between these early weight checks, what are some signs baby needs to be awakened to nurse?

Number of nursing sessions per day: Make sure baby nurses at least 8 times each day (more is even better). Ignore the time intervals between feeds, focusing instead on each 24-hour period. Some thriving newborns sleep for one 4- to 5-hour stretch but still fit in at least 8 feeds by bunching their feeds close together, nursing like crazy while they’re awake (cluster feed). This pattern is common during the first 40 days.[3]

Dirty diapers. Changes in stool color are a reliable sign of adequate milk intake during the first week.[4] If nursing is going well, stools change from black to greenish by around Day 3 and to yellow or brown by Day 4 or 5. If stools stay black and tarry after Day 5, it’s time to contact baby’s healthcare provider to get baby weighed and evaluated. After stools turn yellow, 3 to 4 or more stools per day is a rough indicator baby is getting enough milk, which creates the stools and puts on weight.

If a sleepy newborn does not fit in at least 8 nursing sessions per day, stool color does not change when expected, or baby’s weight is of concern, it makes sense to wake her to fit in more feeds and seek lactation help. When it is difficult to wake baby to feed actively at least 8 times per day, it is time to contact baby’s healthcare provider.

As the months pass, baby may begin sleeping for longer stretches. As her tummy grows, she can hold more milk. Some babies continue to gain weight as expected on fewer feeds per day. Others need the same number of nursing sessions to grow and thrive.[5]

Even if your baby begins sleeping for longer stretches, don’t expect this to continue. With babies and sleep, it’s often two steps forward and one step back. The baby who was sleeping for 5 or 6 hours at night at 3 months is often the same baby who wakes frequently again for night feeds when teething starts and developmental changes (like rolling over, crawling, and walking) occur.

Is it necessary after the newborn stage to wake a baby to nurse? Assuming you’re comfortable, it all depends on how she’s doing. If baby is gaining weight as expected, no need to make any changes. If not, more feeds are likely needed. In some cases, nursing more often during the day might be enough for a baby to get the milk she needs. But if you have what’s called a “small storage capacity” (explained HERE), going for too long between milk removals (nursing or pumping) at night may slow milk production. Getting a sense of your own “magic number” (the number of milk removals per day needed to keep production steady, also explained on the link in the previous sentence) is vital to meeting your long-term feeding goals.[6]

Common Practices to Consider

Some nursing parents worry that if their baby sleeps for too long at night, this might decrease their milk production. But when they are responsive to baby’s cues, if milk production decreases, most babies will simply cue to feed more often to get the milk they need, which also stimulates ample milk production. In short: if you continue to feed your baby on cue, day and night rather than following a feeding schedule (even a loose schedule), extra pumping should not be necessary to maintain milk production. However, some common baby-care practices may interfere with this automatic demand-and-supply regulation of milk-making and cause a decrease production and infant weight gain. Unlike other mammal species, with our large brains, it is not only possible to overthink lactation, we can also be convinced to inadvertently thwart our biology.

Night weaning and sleep training. Making ample milk for our baby (even twins and triplets) is something that usually happens automatically when a baby nurses effectively and nursing parents are responsive to baby’s feeding cues. Even during the newborn stage, however, some baby-care authors advise parents to disregard human physiology and feed babies on a strict schedule, which the American Academy of Pediatrics linked to increased risk of dehydration and slow weight gain.[7] Other authors advise parents to night wean or use sleep-training methods to reduce infant night-waking. These practices involve being less responsive to baby’s feeding cues at night.

These methods may temporarily reduce baby’s night-waking, but they often need to be repeated multiple times as baby enters different stages of growth and development. In addition to being stressful for many nursing parents, depending on their storage capacity, milk production (and baby’s growth) may be compromised as nursing sessions are eliminated. When milk production is no longer automatically regulated by the baby, these practices may prevent families from meeting their long-term feeding goals.

When parents struggle to deal with night-waking, there are alternatives to these practices. An Australian study found that parents were better able to cope with infant night-waking when they learned about infant-sleeping norms and received support.[8] To learn about infant sleeping norms, a good place to start is the free Infant Sleep Info app (details HERE) created by UK infant-sleep researchers at the University of Durham. With this app, parents can chart their baby’s sleep patterns and compare them with other babies their age.

Bottle-feeding and baby’s sleep patterns. Many nursing babies are also bottle-fed occasionally, partially, or exclusively. Depending on how it’s done, bottle-feeding may either reinforce healthy nursing and sleeping patterns or distort them. If paced bottle-feeding techniques (described HERE) are used, this creates an ebb and flow of milk during feeds similar to nursing that helps prevent overfeeding. Bottle-feeding with a consistent, fast milk flow, however, increases risk of overfeeding, overweight, and obesity.[9] If babies are routinely overfed by bottle during the day (a common issue for employed parents), too much milk during their daylight hours can leave babies less interested in nursing at night. This major alteration in normal infant feeding patterns may decrease milk production and interfere with parents’ ability to keep their long-term milk production steady. If this happens, switching to paced bottle-feeding may help get nursing back on track.

Should you wake a sleeping baby? One size definitely does not fit all. As with most aspects of parenting, following a simple adage will never be right 100% of the time. You are the expert on your baby. If your approach is working for your family and enables you to meet your feeding goals, trust your instincts. On the other hand, if a practice doesn’t feel right or negatively affects you or your baby, it’s time to consider alternatives or to seek help.

References

1 Kellams, A., Harrel, C., Omage, S., et al. (2017). ABM Clinical Protocol #3: Supplementary feedings in the healthy term breastfed neonate, revised 2017. Breastfeeding Medicine, 12(3), 188-198.

2 WHO. (2009). WHO Child Growth Standards: Growth Velocity Based on Weight, Length and Head Circumference: Methods and Development. (2006/07/05 ed. Vol. 450). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

3 Benson, S. (2001). What is normal? A study of normal breastfeeding dyads during the first sixty hours of life. Breastfeeding Review, 9(1), 27-32.

4 Nommsen-Rivers, L. A., Heinig, M. J., Cohen, R. J., et al. (2008). Newborn wet and soiled diaper counts and timing of onset of lactation as indicators of breastfeeding inadequacy. Journal of Human Lactation, 24(1), 27-33.

5 Kent, J. C., Mitoulas, L. R., Cregan, M. D., et al. (2006). Volume and frequency of breastfeedings and fat content of breast milk throughout the day. Pediatrics, 117(3), e387-395.

6 Mohrbacher, N. (2011). The ‘Magic Number’ and long-term milk production. Clinical Lactation, 2(1), 15-18.

7 Aney, M. (1998). ‘BabyWise’ advice linked to dehydration, failure to thrive. AAP News, 14(4):21.

8 Ball, H. L., Douglas, P. S., Kulasinghe, K., et al. (2018). The Possums Infant Sleep Program: Parents’ perspectives on a novel parent-infant sleep intervention in Australia. Sleep Health, 4(6), 519-526.

9 Azad, M. B., Vehling, L., Chan, D., et al. (2018). Infant feeding and weight gain: Separating breast milk from breastfeeding and formula from food. Pediatrics, 142(4)