When Is Pumping Too Much, Not Enough, or Just Right?

/I’m often asked the question: “Do nursing parents need to pump in order to make enough milk?” The short answer is no. Effective breast pumps have been available for only about the past 70 years. Clearly humans have successfully nursed their babies for far longer. Also, how many of the thousands of other mammal species need to pump to produce adequate milk? None, of course.

But in some cases, pumping—and/or hand expressing milk—is crucial to meeting lactation goals. The key is understanding when pumping makes sense and how often and how much milk to pump. Too much pumping can lead to painful oversupply. Too little pumping sometimes leads to low milk production, especially when baby nurses ineffectively or the nursing couple is regularly separated at feeding times. Let’s consider this issue from the Goldilocks perspective: When is pumping too much, not enough, or just right?

When Is Pumping Too Much?

Nursing parents anxious about milk production often err on the side of too much pumping. Recently, a mother of a 2-month-old baby asked me when she could comfortably sleep as long as her baby slept at night without needing to pump to relieve her breast discomfort. Her baby recently started sleeping for longer stretches, but uncomfortable breast fullness prevented her from doing the same, not to mention she suffered from recurring plugged ducts.

As we talked, she revealed that soon after her baby’s birth, she began using her all-silicone Haakaa pump at every nursing session—day and night—to collect milk from one side while her baby nursed on the other side (see photo below). At the time, she was collecting 3 or 4 extra ounces (90-120 mL) of milk at each nursing session around the clock, and her freezer was full to bursting. Now I understood why her body would not let her sleep when her baby slept.

I explained that at birth, her body knew how much milk to make based on the number of effective daily milk removals. Although she gave birth to one baby, because she was expressing so much milk so often, her body thought she had delivered twins and was making twice as much milk as her baby consumed.

Before she could be comfortable sleeping for longer stretches, she needed to gradually reduce her pumping until she reached the right level of milk production for one baby, not two. To do this, I suggested she eliminate one daily Haakaa session every 3 to 4 days to give her body a chance to reduce milk production gradually and comfortably. Within 2 weeks or so, she could sleep for longer stretches at night without needing to pump, and her recurring plugged ducts were gone.

How much pumping is too much? On average, pumping once or twice a day is not enough to make a noticeable difference in milk production. But when a baby is nursing at least 8 times per day and a parent adds three, four, or more pump sessions each day, this can generate an oversupply, especially when pumping starts during the first 2 weeks after birth, a period when a birthing parent’s body responds most intensely to mammary stimulation.

Using an all-silicone haakaa pump while baby nurses

Some parents wonder if there can really be “too much of a good thing” when it comes to making milk. Definitely! Oversupply (aka hyperlactation or hypergalactia) is defined as making so much more milk than a normally-growing baby needs that the parent must express milk regularly just to stay comfortable. For this parent, oversupply often leads to painful fullness, recurring mastitis, profuse milk leakage, and painful nipples if baby clamps down during nursing to slow milk flow. For babies, very fast milk flow can make nursing challenging. They may gain weight at double or triple the expected range. Many also develop digestive issues (explosive green, frothy, or bloody stools) and colicky behavior.

A gradual reduction of excess pumping over time as described above can relieve these symptoms without triggering plugged ducts. For many families, slowing milk production to a more manageable level makes nursing a more positive experience for both parent and baby.

When Is Pumping Not Enough?

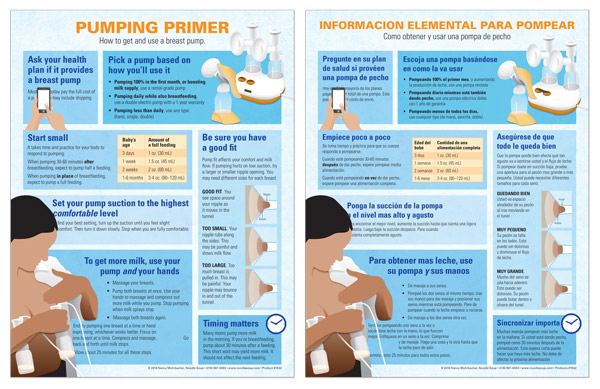

Are there times when more pumping is a good idea? Yes. When a baby is unable to nurse directly or effectively at feeds, pumping can substitute for baby in establishing or maintaining milk production. One example is the baby born so preterm that effective nursing is not possible for weeks or months. In this situation, intensive pumping is required to produce adequate milk, which can be stressful. When pumping substitutes entirely for a nursing baby, to reach full milk production (about 25 oz. or 750 mL of milk per day per baby), parents need to pump early (ideally within the first few hours after birth), often (at least 8 times per 24 hours during the first 2 weeks), and effectively. The hands-on pumping techniques described HERE increase pumping effectiveness by an average of about 50%.

More pumping may also be a good choice when the nursing couple is regularly separated at feeding times, such as when the parent returns to work or school. In this situation, pumping keeps the parent comfortable and prevents leaking milk while also providing the milk baby needs. For more details on how to meet nursing goals even with regular separation, see my book for employed nursing parents HERE.

For parents pumping long term, the key to keeping milk production stable is keeping the number of daily milk removals (nursing plus pumping sessions) at the right level over time. Parents’ “magic number” of milk removals (see my post on that HERE) varies based on the physical difference known as storage capacity. Knowing your magic number makes it easier to meet your long-term lactation goals. For a more in-depth explanation, see my journal article HERE.

When Is Pumping Just Right?

For families who plan to exclusively human-milk feed their baby for the first 6 months, expressing milk may play an important role. When away from their baby at feeding times for any reason, pumping keeps parents comfortable, their milk production steady, and provides milk for their baby. If a nursing problem such as latching struggles occurs, pumping can ensure ample milk until the problem is solved.

Teaching all birthing parents to hand express milk is part of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. By mastering this skill, new parents can relieve any mammary fullness when their sleeping baby cannot be roused to nurse. Expressing a little milk can more quickly reduce any engorgement and prevent plugged ducts. Pumping just “to comfort” (rather than fully draining the glands) as needed can make the early weeks after birth more pleasant as milk production adjusts to the baby’s needs.

On her website firstdroplets.com, U.S. pediatrician Dr. Jane Morton recommends all parents learn to hand express milk during the last month of a low-risk pregnancy. (A pregnancy is sufficiently low risk when sexual relations are not prohibited.) THIS 2017 Australian randomized controlled trial found this practice did not trigger early labor or any other pregnancy complications. Morton also suggests during the first 3 days after birth that parents follow nursing sessions by hand-expressing a little colostrum (the first milk) into a spoon and feed baby this “dessert.” Why? This simple act can prevent three common problems:

©2021 Dr. Jane Morton, used with permission

Excess infant weight loss

Exaggerated newborn jaundice

Delayed increase in milk production

Studies also found that learning hand expression at the end of pregnancy can boost parents’ confidence in their ability to meet their feeding goals. Parents who learned to hand express before birth are less likely than others to use formula in the hospital (study HERE) and are more confident in their ability to produce enough milk (study HERE). See Morton’s instructional videos for learning hand expression during pregnancy at firstdroplets.com.

In other words, even when nursing is going normally, a little pumping or hand expressing is sometimes exactly the right thing to do.

Making Decisions

When is pumping too much, not enough, or just right? This is not a black-and-white issue. Like Goldilocks’ choices, subjective factors play a role. When pondering the best course of action, nursing parents need to consider their situation, their long-term goals, their body’s response, and their individual and family needs. Over time, many of these variables are likely to change, so as with all aspects of parenting, flexibility and an open mind are tremendous assets.